Somehow or other, the history of remarkable women tends to be forgotten. The fact that there have always been smart and determined women who shook off their traditional roles and dared do something new is ignored.

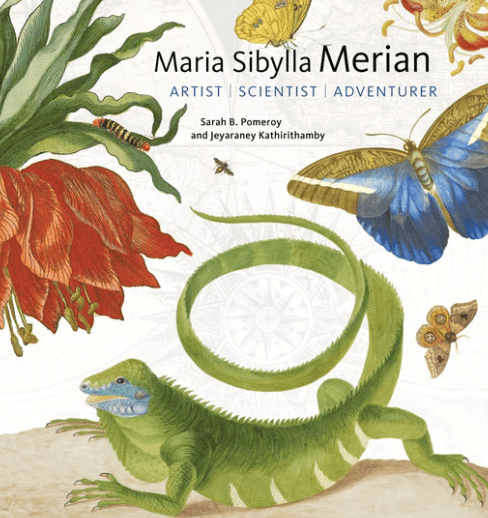

One such woman was Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1719). In her 72 years she was a wife and mother, a member of a fringe religious sect, an art teacher, a scientist and above all a painter of butterflies. She was born in Frankfurt but lived much of her life in Amsterdam. She was born into a privileged class. Her family included Johann Theodor DeBry, an engraver

and publisher.

His daughter Maria Magdalena married Matthias Merian the Elder, an artist. They had 8 children. She died in 1645, and he remarried Johanna Sybilla Heim. Maria Sibylla was their second child. He died when she was three, and her mother remarried Jacob Marrel, a painter and art dealer. Even privileged people suffered unpredictable deaths, and this set of marriages and remarriages was fairly typical.

Maria Sibylla grew up around art. Her stepfather painted books of tulips during the strange Dutch era of tulipmania when some tulip bulbs were worth far more than gold and huge fortunes were made and lost in speculating in tulips. Books of tulips gave buyers a view of what the flowers grown from bulbs would look like. She smuggled paints up to the attic and secretly painted when she was supposed to be sleeping. She snuck out at night to steal tulips to paint, and she was caught in the garden

of a Count Ruitmer. The Count was charmed with her watercolors and let her off in exchange for a painting. From that time her stepfather trained her in painting and taught her techniques such as how to

engrave a copper plate.

She met and married Johan Groff, her stepfather’s favorite pupil, who had just come back from five years in Italy studying architectural painting. She was 18 and he was 28. They had a daughter and moved to Nuremburg. His paintings did not sell, so she supported the family by decorative painting on silk, sold art supplies and taught women embroidery. They had two more daughters, who would themselves become painters.

Maria Sibylla was fascinated by caterpillars and how they morphed into butterflies. For years she brought caterpillars into her house and observed how they developed. In 1679 she published a book of butterfly paintings with notes, titled Caterpillars, Their Wondrous Transformation. Unusually, the book was printed in German rather than Latin, and also unusual, featured paintings of the caterpillars and butterflies on the same page, posed on the plants they actually ate. She and her daughters would hand

color the prints in the book for double the usual price. The work was solid natural history but appears to have also had a sense of how the human soul emerges from the body and arrives in heaven.

She and her daughters moved back to Frankfurt in 1782 because her stepfather died, and her mother had to sell some 300 paintings. Maria Sibylla had a good head for business and sold the paintings. In 1683 she published a second book on caterpillars with more than 100 copperplate

illustrations, and hand colored them for buyers willing to pay more. In 1685 she took her elderly mother and daughters to join the Labadists, a messianic Protestant splinter group. Her husband objected and

she ignored him. He was allowed to divorce her and remarry. She took back her maiden name of Merian, left the colony a year before it collapsed, and moved her family to Amsterdam.

There she gave painting lessons and got commissions to paint flowers from a garden and items from cabinets of curiosities. She decided she wanted to go to the Dutch South American colony of Suriname, which she

knew about from the sect she had belonged to, which unsuccessfully tried missionary work there. She did not have enough money to finance the trip, but most unusually she was given a grant by the city of Amsterdam to go. So in June of 1699 at age 52 and accompanied by her 22 year old daughter

Dorothea Maria, she left for the colony. They did so without a male escort, highly unusual in 1699 even for the relatively progressive Dutch.

They arrived in Paramaribo, the town which the Dutch had exchanged in 1667 for New York City (once called New Amsterdam). The town had a few hundred Dutch settlers and a few thousand slaves. The settlers mocked her but did not interfere. She hired several slaves and an Indian couple and went exploring, after a time in the city painting. She seems to have learned creole, the local dialect. She rented a house, planted a garden and watched as her flowers grew, and collected hundreds of species of plants and caterpillars. She and her daughter preserved all kinds of specimens in alcohol—snakes, frogs, even an iguana and a crocodile.

After two years her health began to deteriorate, so they returned to Amsterdam, with luggage that included a large number of specimens, many paintings, and her journal of Suriname (part of a journal she kept for 30 years). Maria Sibylla did copperplates of paintings of butterflies and other creatures for a book on Suriname, It was done on a subscription basis, patrons paid in advance for their book, which paid for the costs of printing. It was sold for 15 guilders a copy, double for the printed illustrations to be hand painted by her or her daughters.

Her journal is a useful source for anyone researching colonial Dutch Suriname or Dutch ways of life. Her paintings were so exact that modern biologists can precisely identify the species. She died in 1719, a woman who defied convention and lived her life the way she wanted to.

After her death, her daughters came out with a new and expanded edition of the Suriname book. Her daughter Dorothea married the artist Georg Gsell, who became court painter for the Russian tsar Peter the Great. Some of her books have survived and are sold, if and when they go on the market, for large sums. Her work was both scientifically exact and also art that still pleases the eye.

Deep knowledge, every day.

Like, comment and follow : Greg’s Business History.

Happy Reading.

Thanks

Leave a comment